The New Georgia Encyclopedia is supported by funding from A More Perfect Union, a special initiative of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

The excavation of the Singer-Moye Mounds in Stewart County has revealed the buried foundations of Indian buildings that were destroyed and abandoned more than 600 years ago. Thousands of ceramics fragments and animal bones have also been recovered.

Photograph by Elisabeth Hughes, New Georgia Encyclopedia

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

An example of Mississippian Lamar pottery, on display at the Ocmulgee Mounds Visitor Center in Macon.

Courtesy of Robert Foxworth

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The earthen mounds at the Ocmulgee National Historical Park in Macon are the remains of a native culture that lived at the site between A.D. 800 and 1100, during the Early Mississippian period.

Photograph from National Park Service

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Excavation of the Irene mounds site, near Savannah, was led by several important archaeologists, especially Joseph R. Caldwell, who is pictured with an excavation team. Three different shell layers are visible in the earth behind the researchers.

Reprinted by permission of the Coastal Georgia Archaeological Society

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

A group of African American women (pictured in December 1937) helped to excavate the Irene mounds site. The split oak basket, on the right, was made in Savannah especially for this project. The woman in the foreground is smoking a pipe.

Reprinted by permission of the Coastal Georgia Archaeological Society

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

A portion of the largest shell ring on Sapelo Island was excavated in 1950. The trench, cut into the ring by archaeologists, reveals white flecks of shell left behind by the hunter-gatherers who lived on the island during the Late Archaic Period, 5,000 to 3,000 years ago.

Courtesy of Victor D. Thompson

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

An archaeologist stands beside Shell Ring No. 1 on Sapelo Island. The shell rings, circular or semicircular in shape, are too large to be shown in their entirety by a single photograph.

Courtesy of Victor D. Thompson

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Located north of Eatonton in Putnam County, Rock Eagle is an Indian-made rock structure dating back to the Middle Woodland period (300 B.C. to A.D. 600).

Photograph by Brian McInturff

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The chiefdom of Ichisi was located between modern Macon and Perry on the Ocmulgee River. The capital town was probably located at the present-day Lamar archaeological site, a part of Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park.

Courtesy of Georgia Department of Economic Development.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource may need to be submitted to the Georgia Department of Economic Development.

The Etowah mounds were built during the Lamar Period. Modern-day steps allow tourists to climb to the summit of the Etowah mounds.

Photograph by Muora

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Although the original Late Prehistoric earthen platform mound has been completely excavated, a reconstruction of the Nacoochee Mound can be seen today on private property in the Nacoochee Valley.

Photograph by Martin LaBar

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Mississippian Lamar pottery is distinctive because of its unique stamping and shape.

Courtesy of Robert Foxworth

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

An example of Mississippian Lamar pottery. Lamar pottery was made throughout Georgia and well into the adjacent states.

Courtesy of Robert Foxworth

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

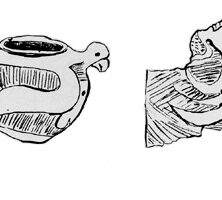

Drawings depict derived effigies with zoned incising found at the Davis Point excavation site at the Kolomoki Mounds. Weeden Island burial mounds are well known for the inclusion of elaborate animal effigy pots in large deposits.

From Excavations at Kolomoki, by W. H. Sears

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The Kolomoki Mounds site in Early County is one of the largest prehistoric mound complexes in Georgia and includes at least eight mounds.

Courtesy of Kolomoki Mounds State Historic Park

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

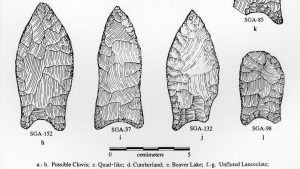

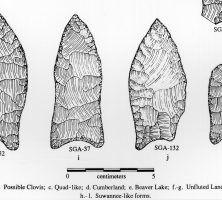

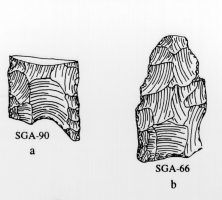

The Middle Paleoindian subperiod features smaller unfluted lanceolate projectile points such as the Suwannee types, among others.

Courtesy of the University of Georgia Laboratory of Archaeology

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

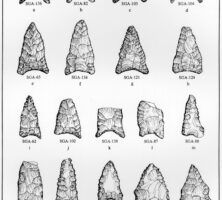

The Middle Paleoindian subperiod features fluted or unfluted points with broad blades and constricted handle elements, which may include the Cumberland type. Fluted points (pictured) have a channel or flute running from the base of the point.

Courtesy of the University of Georgia Laboratory of Archaeology

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

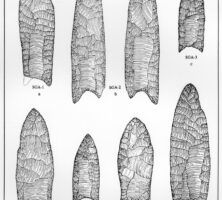

From the Late Paleoindian subperiod come Dalton and related point types, which are characterized by a lanceolate (lance-shaped) blade outline and a concave base ground on the lateral and basal margins, occasionally well thinned. Blade edges are frequently serrated and beveled.

Courtesy of the University of Georgia Laboratory of Archaeology

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

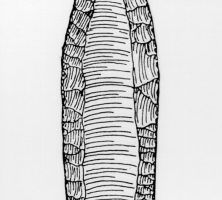

The Early Paleoindian subperiod is characterized by Clovis and related projectile point forms, relatively large lanceolate (lance-shaped) points with nearly parallel sides, slightly concave bases, and single or multiple basal flutes (channels) that rarely extend more than a third of the way up the body.

Courtesy of the University of Georgia Laboratory of Archaeology

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Only one fluted point was found at Macon Plateau, in spite of a massive excavation effort. The fluted point, missing the forward one-third of its length, was of the Clovis type of these artifacts.

Courtesy of the University of Georgia Laboratory of Archaeology

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

This type of pottery originated in northwestern Georgia and is found in small quantities throughout the state. It is from the Middle Mississippian subperiod.

Courtesy of Mark Williams

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Stallings Island, located in the Savannah River eight miles upstream from Augusta, is best known for its very early pottery, a technological development that predated the advent of farming in Georgia by several millennia. Pictured are sherds of the punctated fiber-tempered pottery, ca. 3,800-3,500 years ago. The sherd on top is actually 11 centimeters wide.

Courtesy of Kenneth E. Sassaman

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

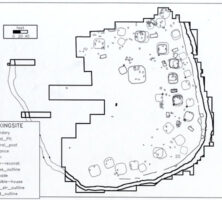

The King site in Floyd County covers a little more than five acres and is bounded by a defensive ditch and palisade. It was first occupied at some time during the first half of the sixteenth century.

Courtesy of David Hally

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Photograph of ceremonial earthlodge which has been reconstructed and is today part of the Ocmulgee National Monument in Macon, Georgia.

Image from Ken Lund

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Archaeological excavation, carried out intermittently at the Etowah mound site for more than 100 years, has unearthed artifacts such as these figures, which have provided much information about life in the Mississippian Period.

Photograph from Wikimedia

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Hernando de Soto was a Spanish-born explorer and conqueror who landed in present-day Tampa Bay, Florida, in 1539 and came to the Georgia area in 1540. Chroniclers of the expedition described the Coosa River valley in glowing terms.

Courtesy of Georgia Info, Digital Library of Georgia.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource may need to be submitted to the Digital Library of Georgia.

Swift Creek pottery is noted for its distinctive decoration. Complex curvilinear patterns were first carved into a wooden paddle, which was used to stamp the design into the soft clay walls of the pottery before it was fired.

Courtesy of Kennesaw State University

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

In 1978 and 1979 the University of Georgia's Department of Anthropology excavated portions of the Cane Island archaeological site before it was flooded. It now lies beneath Lake Oconee in Greene County, Georgia.

Courtesy of W. Dean Wood

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Cane Island, the site of one of the earliest Native American farming villages in Georgia, was located in present-day Greene County along a shallow portion of the Oconee River known as Long Shoals. Wild plants and animals around the river likely supplied most of the food for the Cane Island residents.

Courtesy of W. Dean Wood

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

An illustration of what Sara's Ridge probably looked like during the Middle Archaic Period. The woman in the foreground is cooking with soapstone slabs, while hunters carry a deer toward racks where fish are hung over a fire.

From Beneath These Waters, by S. Kane and R. Keeton

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Archaeologists excavated a prehistoric Indian village in Rucker's Bottom near the Savannah River about 500 years after the civilization's height.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource should be submitted to the Hargrett Manuscript and Rare Book Library at the University of Georgia.

A path leading to two of the mounds at the Etowah Indian Mounds Historic Site. Located in Bartow County, the site is home to the second-largest Indian mound in North America, rises to a height of slightly more than 60 feet.

Photograph from Sharon Meier

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Archaeological excavation, carried out intermittently at the site for more than a hundred years, has unearthed artifacts such as these stone figures, which have provided much information life in the Mississippian Period.

Courtesy of Georgia Department of Economic Development.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource may need to be submitted to the Georgia Department of Economic Development.

The Etowah River, with headwaters near Dahlonega, flows west-southwest for 140 miles to Rome, where it forms the Coosa River when it joins the Oostanaula River.

Image from Kevin Trotman

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.

Modern-day steps lead to the summit of one of the Indian mounds at the Etowah site.

Courtesy of Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Georgia State Parks.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource may need to be submitted to the Georgia Department of Natural Resources.

Archaeologists now recognize that the main occupation of the Kolomoki Mounds site dates to the Woodland Period (1000 B.C.-A.D. 900).

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. Requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource may need to be submitted to the Georgia Department of Community Affairs, Historic Preservation Division.

Ceramic artifacts were found during excavations of the Kolomoki Mounds in Early County.

Photograph by Bubba73, Wikimedia Commons

The New Georgia Encyclopedia does not hold the copyright for this media resource and can neither grant nor deny permission to republish or reproduce the image online or in print. All requests for permission to publish or reproduce the resource must be submitted to the rights holder.